THE 12-man round robin finals of the 2009 Palau chess championship is underway.

The Chess Connoisseur initially reported its commencement in its

August 20, 2009 post. A last minute change in the format, following the suggestion of PNG’s Joselito Marcos, brought about an exciting 5-round Swiss system qualifying event where the top 8 placers joined Palau’s 4 FIDE-rated players in the single round robin finals.

Our correspondent,

Tia Belau’s chess columnist Roberto Hernandez, himself a finalist and among the indefatigable organizers of this year’s event, sent us scores of completed games and results. In his

Chessmate column in the country’s weekly newspaper, Hernandez reported that those who failed to make it to the finals play in the consolation group, also a round robin event with prizes for winners.

The nature and the schedule of work of chess participants prohibit all games of a round to be completed on a single day. In the consolation group, one contestant withdrew his participation because of conflict in his job schedule. Hernandez explained ‘Palau has the most flexible chess schedule in the world to accommodate ALL players whatever their schedules are.’

Despite the explanation the player still withdrew from the formal competition. Before leaving, however, he played–and won!–a couple of games with bets against an available finalist.

Games are played in two venues and participants play against whoever is available regardless of round because of the all-play-all format. As such only provisional standings can be shown because of different number of completed games per player.

Well, that’s Palau chess!

Here are the latest interim standings of 2009 Palau Chess Championship.

1. Jun Mahor 2½/4

2-4. Roberto Hernandez 1830 2/3

Menandro Manuel 1942 2/2

Cyril Montel, Jr. 1870 2/2

5. Romeo Caballes 1½/5

6-9. Bernard Garcia 1/1

Masum Billah 1/4

Gene Pastrana 1870 1/1

Paquito Suringa, Jr. 1/3

10. Michael Mercado ½/1

11. Elpidio Manaligod ½/2

12. Craig Dittrich 0/2

Here are some selected games from the ongoing event.

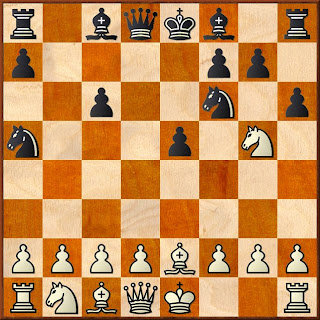

An upset right on the first day of the championship finals was in the making when top qualifier, Michael Mercado (Black), who topped the qualifying event with a perfect score of 5 points, found himself in this position against qualifiers’ runner up Jun Mahor.

Diagram 1 – Position after 29… Kh8.

Diagram 1 – Position after 29… Kh8.

White went pawn hunting and overlooked a forced mate in five moves:

30.Rh7+! Kxh7 31.Qd7+ Qe7 32.Qxe7+ Rf7 33.Qxf7+ Kh8 34.Qg7#! After

30... Qe3+ 31.Kf1, Black himself came up with a rook sacrifice of his own with

31… Rxf3+! which was only good for a draw but enough to keep his unbeaten streak. A draw could still be achieved without sacrifice through queen checks but Black wanted to get it with flourish. The game concluded with

32.gxf3 Qxf3+ 33.Kg1 Qd1+ 34.Kh2 Qxc2+ ½–½.

Equal second seed,

Cyril Montel Jr (FIDE rating, 1870), registered the shortest victory so far —a 20-mover—in his game against

Paquito Suringa Jr. It could have been shorter by 4 moves if only Montel (Black) found the forced mate on his 11th turn.

Here is the game with light notes from

The Chess Connoisseur.

1.d4 Nf6 2.Nc3 g6 3.e4 d6 4.d5?

An early mistake. Against the principle of moving the same piece twice, this move aggravates the infraction by unnecessarily opening up the a1-h8 diagonal for Black’s fianchettoed bishop.

4… Bg7 5.Bd2 c6 6.Bc4?Another inaccuracy, which Black exploited to initiate an attack on White’s king. Better was 6.Nf3 0–0 7.Be2 Nbd7, but Black still has a slight edge.

6... b5 7.Bb3 b4 8.Nce2?White could have maintained material equality with 8.Na4, but Black has a clear advantage.

8... Nxe4 9.Bxb4

If 9.Nf3, then 9… Bxb2 wins.

9... Qb6!

Hitting simultaneously the bishop at b4 and the f2-square which effectively decided the game. White must give up a piece to avert the threatened mate at f2.

10.Nd4 Bxd4 11.Bxd6Surrendering another piece. Instead if 11.Bd2, Black weaves a mating net starting with 11… Bxf2+ 12.Ke2 Ba6+ 13.Kf3 Nd7 14.g3, and now the surprisingly sparkling move 14… Bf1!! finishes off White.

Diagram 2 – Position after 11.Bxd6?

Diagram 2 – Position after 11.Bxd6?

A rather prosaic way of winning the game. Instead, Black has a forced mate in five moves with

11... Bc3+!! 12. Ke2 (

12.bxc3 Qxf2#)

12... Ba6+ 13.Kf3 (

13.Bc4 Bxc4+ just prolongs the game by one move)

13… Qxf2+ 14.Kg4, and Black has choices of mate among

14… h5+ 15.Kh3 Ng5#;

14... f5+ 15.Kh3 Ng5#; and

14... Qf5+ 15.Kh4 Bf6#.

12.Nf3 Bxf2+ (

Still missing the decisive 12... Bc3+!)

13.Kf1 Ba6+ 14.c4 0–0 15.Qe2 cxd5 16.Rd1 Nd7 17.Rxd5 Ndf6 18.Rd3 d5 19.Rd1 Ng4 20.Rd3 Nxh2+ 0–1Disaster struck when fourth-seed

Roberto Hernandez (White), a whole rook up, suffered an upset loss against qualifier

Masum Billah, a Bangladeshi.

Diagram 3 – Position after 25… Kg6

Diagram 3 – Position after 25… Kg6

Good only for a draw. The order of the day was to bring the queen back to action with 26.Qe8+. After 26… Kf5 27.Rf8+ Kg4 (

if 27... Ke5 28.Qb8+ Ke4 29.Qd6! wins), then 28.Qb5! (

A difficult-to-visualize continuation in the midst of checking the opponent’s king) 28… Qe3+ 29.Rf2 Kxg3 30.Qf1, defends White’s king and keeps his attack on.

26... Kf5 27.Rf8+??

The losing moment. White checked with the wrong piece that led to his downfall. Correct was 27.Qf8+! Nf6 28.Qxg7 Qd1+ 29.Kg2 [but not 29.Kh2??, or 29. Kf2??, because of 29… Ng4+ 30.Kg2 Qe2+ 31.Kg1 Qf2+ (

31... Qh2+ 32.Kf1 Qf2#) 32.Kh1 Qh2#] 29... Qe2+ 30.Kg1 Qe1+, with equality.

27... Kg4! 28.Rf2 (

28.Qb8 Nf6 wins)

28... Qe1+ 29.Rf1 Qxg3+ 30.Kh1 Kh3 31.Qxd5 exd5 0–1

Games between players without much tournament exposures usually lead to comedy of errors. The winner in the following game, as Savielly Tartakover once said, was ‘the player who made the next to the last mistake.’

Mahor,Jun - Garcia,BernardPalau Chess Championship, Koror, 18.10.2009

The moves leading to the diagram were:

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.a3?! When an amateur plays a move like this annotators readily put a question mark, while if a professional does it an interesting move “!?” is appended. A case of double standard in annotating games. 3… Nd4 4.c3 Nxf3+ 5.Qxf3 Nf6 6.d4 d6 7.h3 c6 8.Bg5 Be7 9.Nd2 Qb6 10.Nc4 Qc7 11.Bd3 Be6 12.0–0 Bxc4 13.Bxc4 Qb6 14.dxe5 dxe5 15.Qf5 Qc7 16.Bxf6 Bxf6 17.Rad1 0–0 18.Rd7 Qc8 19.Rfd1 b5 20.Ba2 a5 21.g4 h6 22.h4 Bxh4 23.Bxf7+ Kh8 24.Qg6 Bf6 25.Be6 Qe8 26.Bf7 Rxf7 27.Qxf7 Qc8 28.f3 Qa6 Diagram 4 – Position after 28... Qa6.

Diagram 4 – Position after 28... Qa6.

Better was 29.g5! If 29… hxg5, then 30.Kg2 g4 31.Rh1+ Bh4 32.Qxg7# (32.Rxh4#).

29... Rg8 30.g5!?One move too late. Better was 30.R1d6! b4 31.c4 Qc8 32.Rxf6! wins.

30... Bxg5 31.Qg6It is still not late for 31.R1d6. White wins after 31… b4 32.c4 Qa8 33.Rg6 Qe8 34.Qxe8 Rxe8 35.axb4 axb4 36.Rxc6.

31... b4 32.Kg3

32.Qxg5! wins.

32... Qe2 33.Rg1??A blunder. The correct move, 33.Qxg5, still wins for White.

33... Bf4+!

Turning the table.

34.Kg4 Qf2?Black’s turn to err. Instead, 34... Bh2! wins.

35.Kf5 Qxf3 36.Ke6 Qh3+ 37.Rg4??White blundered anew and failed to make the most of his chances. Instead, 37.Qf5 Qxf5+ 38.exf5 would give White a slight advantage.

37... h5!It’s all over. The game concluded with

38.Rxg7 Qxg4+ 39.Qxg4 hxg4 40.Rc7 Rg6+ 41.Kf7? Rg7+ 0–1.

.

Photo: http://ugra-chess.ru

Photo: http://ugra-chess.ru

Photo: http://www.ugra-chess.ru

Photo: http://www.ugra-chess.ru